Managing Product Obsolescence

In my opinion, technology companies do not invest enough time and resources in the research and ongoing improvement of their product development processes. This is my experience across many industries over an almost 30-year technology career.

It’s easy enough for companies to say “Well, there are a lot of areas where we’re not investing, but probably deserve our attention.” An increase in spending on channel development, for example, would undoubtedly increase sales. Better funding of distribution systems would help streamline a firm’s delivery within established channels. And spending more on internal education and training programs has been proven to strengthen an organization’s ability to innovate, if not improve overall team morale.

But nothing affects a company’s bottom line more fundamentally than positive adjustments made to the enterprise’s product development lifecycle – especially those changes that affect how a company manages products and services already on the market. Most organizations are continuously tinkering with the design, build, and deployment of their products and services, but few companies take a few steps back to review their overall operations, and how best to guide their offerings through that lifecycle.

But nothing affects a company’s bottom line more fundamentally than positive adjustments made to the enterprise’s product development lifecycle – especially those changes that affect how a company manages products and services already on the market. Most organizations are continuously tinkering with the design, build, and deployment of their products and services, but few companies take a few steps back to review their overall operations, and how best to guide their offerings through that lifecycle.

What are the stages of your lifecycle? What are the indicators for determining when to move your product into the next stage, or when to replace it? How do you gauge your product’s life expectancy, and what happens when you reach that final stage? How do changes to operational, marketing, or sales strategies affect your product metrics?

Once you have the ability to see this information and generate scenarios based on these strategies, you can more efficiently and effectively plan for obsolescence and develop new product/feature tactics – and unlock unrealized revenue that had otherwise been lost within the shuffle of deficient lifecycle planning.

Planning for Obsolescence

It’s actually a very simple model: every product or service has a limited shelf life. To maximize its shelf life, you must be able to do more than track its progress while in production. Many decisions about your offering must be made well before this stage. Every manufacturing organization understands that you cannot sit and wait for a product to venture through its life on its own. You must know when to introduce the product or service to the market, recognize the transition to maturity, and redesign or replace it with another product. The tricky part is recognizing where your offering is within its lifecycle, and how changes to industry and operational factors can affect the lifecycle.

To maximize your revenue opportunity, timing is everything.

This is not a new concept. Talk to any marketing major, and they’ll walk you through each of the phases a product goes through, illustrating some of the common signs of product maturity and decline – traits that can help you recognize the transitions. Unfortunately, there is no science behind this. There is no manual that can tell you when a product or service should be phased out. While the field of supply chain optimization tools is large and growing, these solutions address management of the supply chain itself: forecasting, inventory, purchase orders, trading partners. With the rapid adoption of social platforms, organizations are intuitively aware of the value of improving communication across the product lifecycle, though they may not know where those impacts are improving key metrics, even something so obvious as improved time-to-market. Few companies take the time to really investigate and develop solutions to measure and manage an individual product’s lifecycle.

This is not a new concept. Talk to any marketing major, and they’ll walk you through each of the phases a product goes through, illustrating some of the common signs of product maturity and decline – traits that can help you recognize the transitions. Unfortunately, there is no science behind this. There is no manual that can tell you when a product or service should be phased out. While the field of supply chain optimization tools is large and growing, these solutions address management of the supply chain itself: forecasting, inventory, purchase orders, trading partners. With the rapid adoption of social platforms, organizations are intuitively aware of the value of improving communication across the product lifecycle, though they may not know where those impacts are improving key metrics, even something so obvious as improved time-to-market. Few companies take the time to really investigate and develop solutions to measure and manage an individual product’s lifecycle.

Every product and service has a limited shelf life. The time to innovate/extend/replace an existing offering can be determined when market indicators show one product to be approaching its production decline, while another product is reaching maturity. The sweet spot is that point where the declining product overlaps the expanding product, replacing the decreasing revenues. The ability to read market indicators and stagger releases not only ensures efficient use of resources and working capital, but it also optimizes revenue of an offering. You don’t want to spend millions on advertising for a product or service in decline, for example, that could be used to bolster sales or operations of a newer version that is reaching revenue maturity.

Extending Product Shelf-Life

The key characteristics that underscore a more agile product development strategy include:

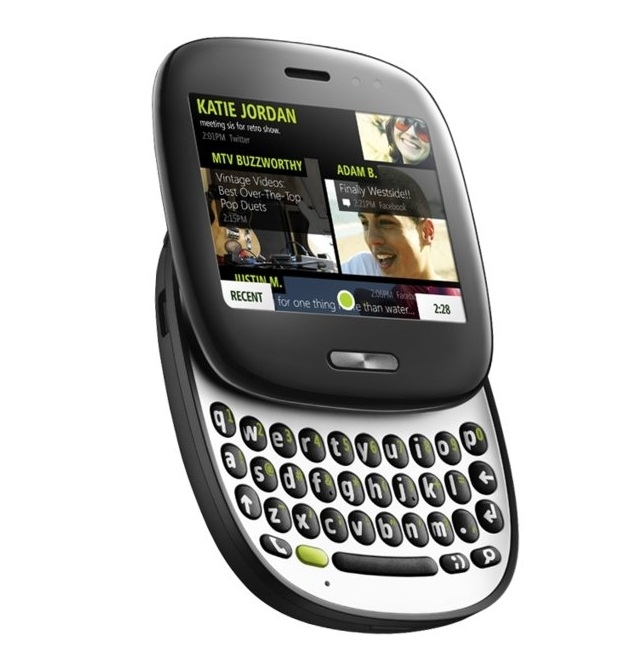

- Short, effective lifecycles – for consumer and hardware-based products, this typically means less than 6 months, which implies that time-to-volume is a critical consideration. For software and online solutions, it might mean every 4 to 6 weeks.

- Rapid adjustments to market needs – market needs can be driven by two factors: customer requirements and technology availability. Both contribute to accelerating the speed at which preferences and needs change in the marketplace.

- Configuration-based products – products must possess certain flexibility so that last minute substitutions can be made. This allows for manufacturing strategies, such as “configured to order”, “delayed differentiation”, and “postponement” which are prevalent in most consumer electronics segments, as well as the broader computing and storage industries.

What all of these factors point to is revenue optimization. In a world of razor-thin margins, missing a sale can mean losing a contribution margin. McKinsey & Company, a leading management consulting firm, provided some key insights on product lifecycle management by providing a comparison between the high-tech electronics industry and another industry with short lifecycles – the fashion industry:

- In the high-tech electronics industry, missing a sale due to poor product transition can translate into a loss in contribution margin ranging from 25% – 30% of the producer’s sales price. In the fashion industry, the impacts can be even greater, with lost contribution margins closer to 40% – 50%. In both of these industries, delays can be costly. For example, one leading manufacturer delayed the launch on two of its flagship products due to a poor product transition strategy. By the time it ramped up production, it had lost around $300 million in potential sales.

- Managing product obsolescence costs is particularly critical in the high-tech electronics and apparel industries. Obsolescence costs are incurred when finished products or raw materials become obsolete and need to be cleared out of inventory. Electronics on the shelf lose as much as 10% of their value each month. A top technology manufacturer might improve margins $100 to $200 million on revenues of $10 billion by understanding and aggressively managing the obsolescence stage of their product’s lifecycle. In the fashion industry, one time end-of-season sales can mean discounts as high as 30% to 70%, which is why leading operators handle obsolescence by discounting slow-moving items on a ongoing basis.

Building a House of Quality

In the consumer electronics industry, companies often need to manage worldwide product launches – sometimes across dozens of countries or more. The level of complexity in these product transitions is very high. A manufacturer must coordinate activities aimed at different market windows among many regions and countries, and at the same time avoid demand cannibalization and regional price pressures. With all of these concerns, companies often lack insight on the most profitable products in their own portfolios. With a lack of visibility into their product lifecycles and no compelling data to guide them, a common practice is for companies to mistakenly dedicate resources to manufacturing and selling these low margin products – at the expense of lost revenues from their star products.

In business school, we learned about the “House of Quality” (HOQ) planning matrix, which originated in the early 1970’s from Mitsubishi as part of the management approach known as quality function deployment (QFD). In an HBR article by authors John R. Hauser and Don Clausing (1988), they point out that HOQ had been “used successfully by Japanese manufacturers of consumer electronics, home appliances, clothing, integrated circuits, synthetic rubber, construction equipment, and agricultural engines. Japanese designers use it for services like swimming schools and retail outlets and even for planning apartment layouts.”

In business school, we learned about the “House of Quality” (HOQ) planning matrix, which originated in the early 1970’s from Mitsubishi as part of the management approach known as quality function deployment (QFD). In an HBR article by authors John R. Hauser and Don Clausing (1988), they point out that HOQ had been “used successfully by Japanese manufacturers of consumer electronics, home appliances, clothing, integrated circuits, synthetic rubber, construction equipment, and agricultural engines. Japanese designers use it for services like swimming schools and retail outlets and even for planning apartment layouts.”

Also known as the “Quality Matrix,” the purpose of the HOQ is to provide a simple method for converting customer needs into technical descriptors. The matrix helps planning teams to outline their customer requirements and technical descriptors, establish the priority of the various descriptors, identify relationships between the descriptors, and then assign target values for each descriptor. This scoring method helps organizations to better understand and evaluate competitive features and products, and in my own experience with the HOQ, often highlighted high-impact features that were viewed as low-priority or not part of the product roadmap at all.

The HOQ may not be the right answer for your product or service planning — the idea is to consider new tools and methods that might help your team overcome planning roadblocks, and look at your current offerings in a new light.

Nothing affects a company’s bottom line more fundamentally than inefficient management of products already in the marketplace. Companies need to develop strategies to address the need for increased visibility into the product lifecycle. This kind of visibility will enable them to create product scenarios based on certain metrics, and make better decisions about when and how they launch or retire any given product or service.